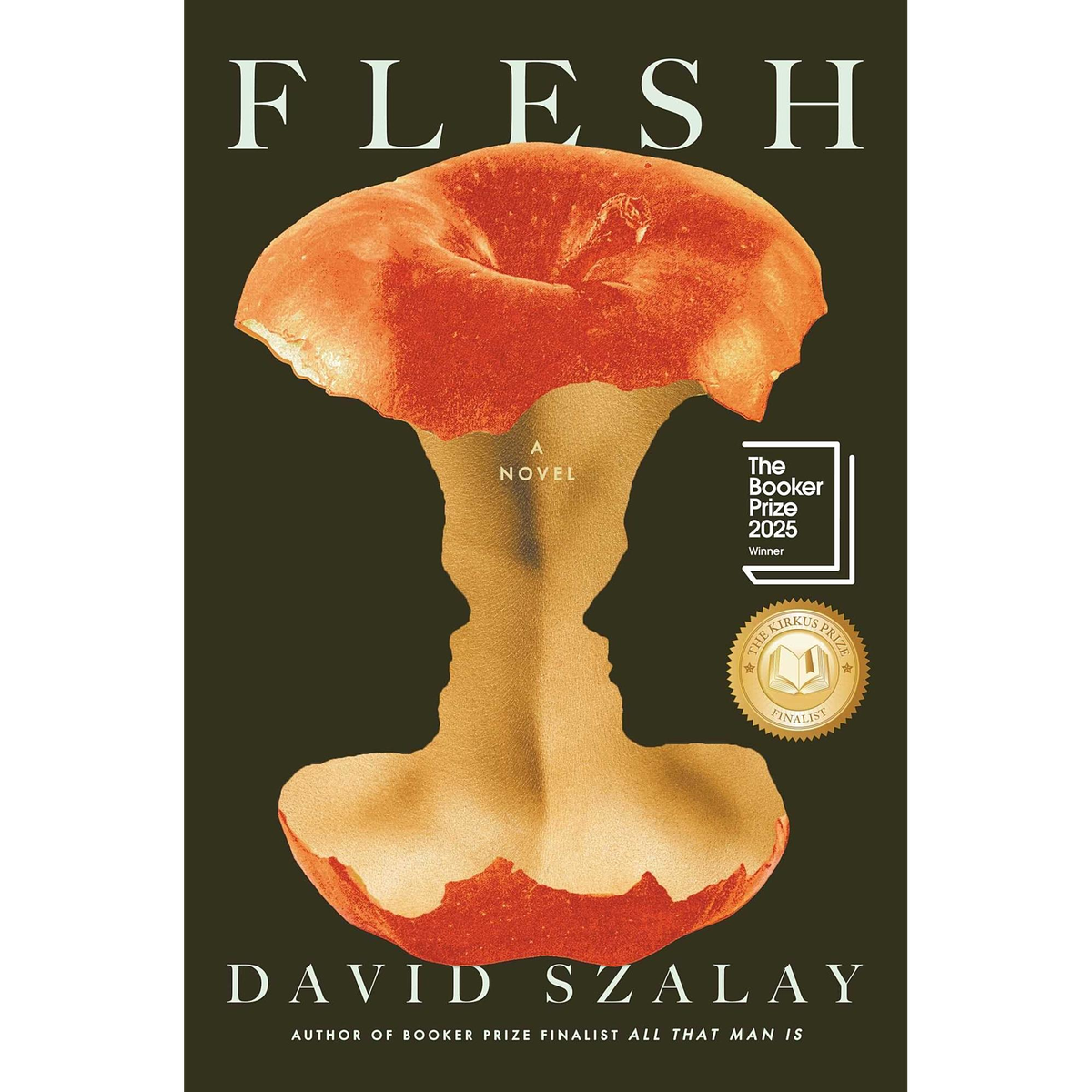

Flesh: A Novel, by David Szalay

These are scary times for men.

Successive waves of feminism have been crashing against the cliffs of patriarchal philosophy for decades now, and their erosive progress is evident. This has put subscribers to traditionalist views in a panic. Some of these traditionalists have responded by dreaming up horrible scenarios of women overseers dressed in leather bondage gear and tall stilettos cracking whips at loinclothed men on their knees. (Pretend not to notice their erections.) More practically minded male supremacists are busy building a fortress on Philosophy Island: the impregnable Manosphere. It is safe in this bubble, and its monastic inhabitants are free to hype each other up, complimenting each other’s physiques, virility, and heroism. (Again, ignore the erections.)

István, the protagonist of Flesh, is everything you could ask for in a champion of the manosphere. He is a man with a great physique, endless virility, and medalled heroism. His jobs in the military, as a bouncer, and in private security are manly ones where he can protect the weak and inflict physical violence on his adversaries. And best of all, he is a white European (although we don’t like to talk about why that’s good). Surely he is the one who can take back the territories of Philosophy Island that have been seized by the invading females!

Luckily, if conquering a woman can be done by fucking her, then István is truly one of God’s strongest soldiers. He is a sex addict who cannot help but parlay any interaction he has with a woman into a sexual encounter. Flesh is, appropriately, something of István’s sex journal; its narrative timeline is advanced by each new sexual conquest as much as it is any other plot point.

To us readers who don’t have a particularly strong image of the chiseled Adonis that István must be, it’s a wonder that he is able to seduce any women at all. Listening in on István’s conversations has the same compelling energy as watching paint dry. His dominant contributions to dialogue are “Okay”, “Don’t know”, and “Yeah”, and seeing him put more than five words together in a sentence is like coming across a desert oasis. Szalay cleverly steers the reader around any situation where István might be forced to monologue, such as when István tells his therapist about the wartime incident, by passing the scene off to the narrator.

The effect is remarkable. Although he is such a manly man, István is presented as a dullard with no interiority. He depends almost entirely on his interlocutors to make conversation and decisions for him, and rarely does he have an opinion or emotion all to himself. When left truly to his own devices, he turns off the single neuron in his brain and goes for a smoke.

Of course, we know that there is a deep-seated reason for his maladjustment. Szalay begins the story by subjecting István to a series of statutory rapes at the tender age of fifteen, an unresolved trauma that seeps into every facet of István’s life. Manosphere devotees might cheer at the opportunity for a teen boy to have several sexual encounters with a knowledgeable, sexy cougar, but Szalay, in a biting inversion of the rape-as-character-development trope so often used for women, shows us just how fucked up it makes István.

His nymphomania is clearly derived from his rapist’s linkage of mundane chores (grocery shopping) with sex acts; as an adult, István is thus incapable of untangling sex from any mundane aspect of life. Towards the end of his relationship with his rapist, István, inexperienced at parsing complex emotions and overwhelmed by hormones, convinces himself that he is in love with her and consequently kills her husband. This in turn transforms into István’s dulled sense of self, limited emotional range, and lack of ethical boundaries. And there is his apathy towards even the smallest choices and decisions in life, which we can understand as the consequence of his rapist’s removal of consent. Because István’s participation in the rapes was not a meaningful choice, he becomes unable to make meaningful choices as an adult.

Ironically, this lack of agency snowballs into István’s initiation into the nouveau riche. Although he has no particular skills and no ambition, István is handed successive opportunities to climb up the ladder. Agreeably, he takes them, and is soon catapulted from small-town drug mule gigs to multimillionaire status in London’s richest circles, where he rubs elbows and exchanges bribes with government officials. Once again, he is a poster child of the manosphere movement: a rags-to-riches success who colored outside the lines and was rewarded with wealth and power.

Szalay is not a benevolent god, and he visits terrible cruelty on his protagonist once again–this time, at the height of István’s ascent. Easy come, easy go, and in a matter of pages István is broke and his legacy destroyed utterly. Left with nothing but his sunset years, István putters on with a dead-end job, no friends, and a single fleeting lover. Even his long-suffering mother, the only character who deserved more, passes away.

It seems that in our haste to encase ourselves in the manosphere bubble, we have forgotten about that stalker in the night who can pass through walls: the male loneliness epidemic. István may have been the ideal alpha man, but Szalay reminds us that this means nothing. His empire is dust. He does not live any beatific life. He has made no contribution to society, bettered no lives. He simply continues, alone, waiting for the end.

Plot: 2 / 5

Themes: 4 / 5

Prose: 4 / 5