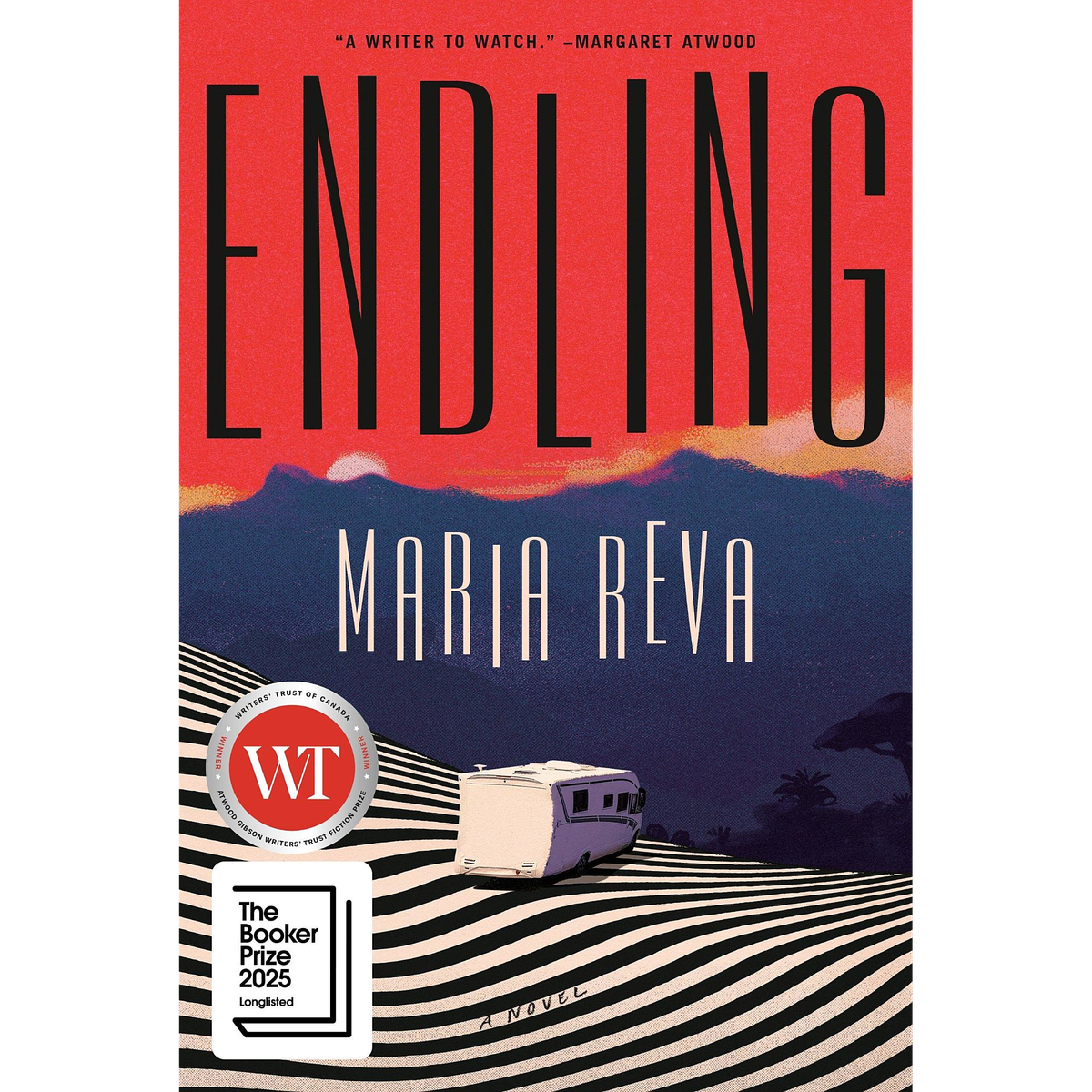

Endling, by Maria Reva

It’s a disservice to reduce Endling to a simple novel. It’s revision as performance, the unimaginably talented Reva rewriting her work live for the reader even as she has new thoughts and receives new information in real time. We observe her raw process and are transfixed as we watch her argue with her agent, crumple up weak drafts, and enter the field to do her own investigative research. We have no choice but to follow her rapid changes as she offers first a blue-tinted film to filter our view, then a red one, then snatches both away, then layers both in front of our eyes, each time revealing a new story, a new interpretation, a new perspective. What’s real? Or, perhaps: what isn’t?

Reva informs us that Endling was supposed to be about romance tours, the common practice of meet-and-greets for foreigners seeking a slightly more legitimate way to find a Slavic mail-order bride. The book starts with one of her thinly veiled avatars, Yeva, getting into romance tours as a great way to make quick under-the-table cash. A scientist researching endangered snails, she desperately needs the money to fund her mission of finding and saving endlings, the last living members of near-extinct species.

The story expands with two barely-of-age sisters, Nastia and Sol. They have been abandoned by their mother, a feminist activist who has disappeared after a streak of anti-romance-tour performance protests. To spite her missing mother, Nastia decides to make a living by working the romance tours herself, and Sol, a bookish scholar, acquiesces as long as she can keep an eye on Nastia by posing as her translator.

Nastia, seeking to draw out her mother with a splashy stunt, conspires to kidnap a number of the bachelors attending her latest romance tour. She reaches out to Yeva, coincidentally a bride on the same tour and whose mobile lab Nastia has decided is the perfect vehicle for the stunt, and Yeva, moved by a sisterly instinct, is eventually drawn in as a fellow conspirator.

The first step of the plan goes more or less as planned, and soon the three women are speeding off in Yeva’s lab with a baker’s dozen of confused foreign men locked in the trailer. It is at this very moment that explosions announce Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Here, we need to put the book down and breathe for a minute. This new development is less a baseball pitch out of left field and more of a wrecking ball. It is simply too real. There is supposed to be a protective membrane of fiction around this narrative, a fourth wall. And the Russians have just crashed through it with the same disdain that they had for the Ukrainian border. How can we make sense of this? How can such a heavy, current, and political topic be reconciled with the screwy buddy comedy that we were engaged with just a moment ago?

Maria Reva has the same question and no answers. She is as lost as we are. Romance tours, while an interesting and controversial topic, were not making global headlines or lists of top humanitarian crises even when there wasn’t a war at hand. And now that there is, the topic seems totally pointless and unimportant: a crooked painting in a house on fire. What the hell is the point of continuing the story? What is the point of writing any story right now?

We watch in silent solidarity as Reva struggles to distill some clarity from her work. To make it even more frustrating, she doesn’t have time or focus; her grandfather is still in one of the battleground cities in Ukraine, and she must get him out. How? He’s stubbornly ensconced in his apartment, just like the lone snail, hiding in the knots of a withered acacia tree, that Yeva has spent years searching for. And in a reflection of the bombings threatening to make Reva’s grandfather another casualty of the war, the snail’s acacia is lit on fire. Time is running out.

At this point, fiction and memoir cannot be untangled. Every character is a manifestation of Reva, and in fact some characters are actually just her popping into the story, a humbug momentarily peering out from behind the mask of the Wizard. Even when they are not literally her, Reva’s characters mirror her motivations, movements, and actions–or at least until Reva realizes that she has accidentally (?) been writing about herself, and guiltily rewrites her scenes. The effect is dizzying: a kaleidoscopic representation of Reva’s interthreaded stream of consciousness, memory, and living experience.

Plot: 4 / 5

Themes: 5 / 5

Prose: 4 / 5